Last month, in a televised interview, yoga guru-turned-businessman and staunch Bharatiya Janata Party supporter Swami Ramdev termed anti-caste activists “intellectual terrorists”. Since then, social media has been filled with criticism. People have been citing icons of the anti-caste movement such as Periyar EV Ramasamy and BR Ambedkar to slam the votaries of Hindutva.

The comments of Ramdev are in synch with the incidents in which Periyar, and other icons, have been destroyed or dishonoured. In March 2018, Periyar’s statue was vandalised by BJP supporters in Vellore in Tamil Nadu. The vandalism came right after BJP leader and rabble rouser H Raja’s Facebook post declared Periyar the next target of Hindutva mobs after Vladimir Lenin’s statue in Tripura was bulldozed by a mob wearing saffron caps. In September, a lawyer defaced Periyar’s statue at Mount Road in Chennai, Tamil Nadu.

Not only this, anybody who writes about Periyar is opposed by BJP and its allies. Last year, Ahmedabad University announced the appointment of noted historian Ramchandra Guha as the director of the Gandhi Winter School at its faculty of Arts and Sciences. Immediately, BJP’s student wing ABVP sprung into action and opposed his appointment. Guha’s book, Makers of Modern India, according to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s student offshoot, ABVP, “divides” the country. The book contains a chapter on Periyar and how his social reform ideas helped the country re-imagine its future. Eventually, Guha did not join the university.

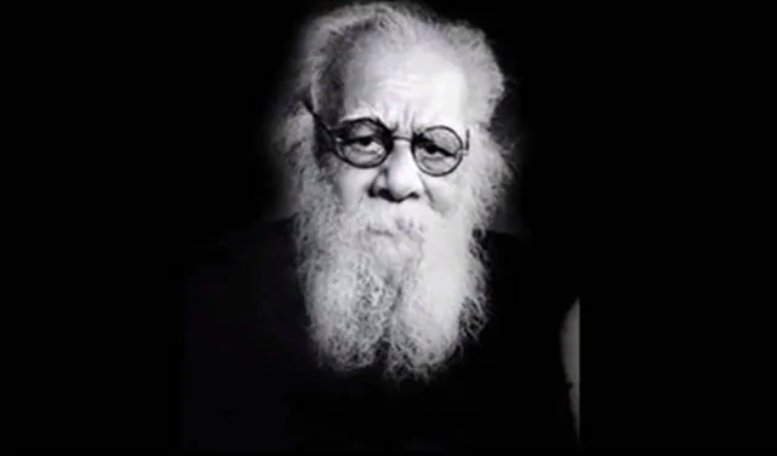

Why is Periyar, the Socrates of Asia, opposed by BJP? Is it surprising that one who identified Brahmanism as the root cause of social evils in society is hardly known amongst the Dalits in the North? These are the questions that arise today, on the 46th death anniversary of Periyar on 24 December 2019.

Largely, North Indian Dalit politics has revolved around BR Ambedkar and Kanshiram. Statues or other images of Jyotirao Phule may still be found in the northern states, but Periyar remains, basically, anonymous. What the BJP is achieving by opposing his ideology is putting Periyar’s name down in the scheme of things.

Periyar was among the leading social reformers of the 20th century, a declared atheist who proclaimed that there is no god. Born into a religious Hindu family, Periyar became a staunch opponent of religion from an early age, and attacked the evils of Brahmanism and Hinduism. He discarded idol worship, did not believe in Vedanta or the Hindu philosophy. He not only burnt religious texts but also considered Ravana as his hero. “He who created god was a fool, he who spreads his name is a scoundrel, and he who worships him is a barbarian,” he said.

Periyar inspired people of non-elite castes by starting the self-respect movement aimed at imparting equal human rights to all citizens. In his speeches, he emphasised upon women’s right to use contraception, divorce and remarry, at a time when Indian society was aligned against the idea of birth control or divorce.

Periyar wrote in critical accounts on the Ramayana and other Hindu texts that they misinform people about the superiority of Brahmanism and promote the caste system. He targeted Brahmin priests who, according to him, were corrupt, devious and prone to excessive sexual tendencies.

Influenced by the principles of Gandhi, Periyar joined the Congress. But left after six years as he found that Congress was dominated by elite-caste Hindus who controlled most of the party’s key positions. The trigger for his leaving the party was also the refusal to entertain the notion of reservations in government jobs and education. During those days, in Congress-run hostels, Dalits and elite-caste Hindus had separate kitchens, which he opposed. His plans to raise the representation of Dalits in the Congress found little coinage. Incidentally, around the same time that Periyar left the party, the Vaikom issue exploded on the scene.

At a Shiva temple in Vaikom, (now in Kerala state), Dalits were prevented from offering prayers. Even the public roads leading to the temple, which is located close to present-day Kottayam, were closed to the Dalits. An 1865 notification by the government ended this obstruction, and reaffirmed it in 1884. The High Court ruled that the earlier caste-based restrictions were to continue. Efforts had been made by the non-elite caste members to break this restriction since the early nineteenth century. Around a quarter-century later, the Congress offered this movement its support, demanding that the restrictions be withdrawn.

Periyar became pivotal to this “Vaikom Satyagraha”, which started in 1924. The primary initial aim of the Satyagraha was to defy the restriction on entry into the area surrounding the temple. This period saw multiple confrontations between the Brahmins and the elite-caste leaders. After the front-line leaders such as TK Madhavan, a journalist and follower of Shri Narayana Guru, and KP Kesava Menon, a follower of Mahatma Gandhi, were arrested along with other leaders, Periyar took the movement in his hands and led it fiercely. Twice he was arrested. After the Vaikom Satyagraha, people gave him the title of Vaikom hero.

The Vaikom Satyagraha was probably one of the first instances where Periyar had a face-off with Congress. Mahatma Gandhi wanted the movement to remain a local affair. Joseph Lelyveld mentions in his book, Great Soul, that “Gandhi now took the view that struggle at Vaikom could not be considered an appropriate Congress project. The national movement, he said, should not come into the picture.”

Historians such as Guha believe that Gandhi did not sideline the movement, though pressure was building up and there were strong demands from Dalits and others to lead the movement. Though he went there, he could not gain any victory in seeking the entry of Dalits in the temple. It was only after a decade that Dalits gained access, when the Travancore Darbar announced that the temple is free for all to visit. Gandhi’s Satyagraha came under intense re-evaluation, while this movement made Periyar the messiah of Dalits.

Vaikom was not the first socio-political protest. The first came around 1912 with the setting up of the Madras Dravidian Association. Its aim was to cooperate with British in India to gain concessions for non-Brahmins. In 1916, the South Indian People’s Association (SIPA) was formed, which laid down the grievances of non-Brahmins and urged them to fight for their rights. In the same year, 1916, political stalwarts such as TM Nair and SRP Theagarayar formed the Justice Party—which eventually came under Periyar’s control, and he transformed it into the Dravida Kazhagam, a non-electoral social movement.

After he left the Congress, Periyar joined the Justice Party. Under him, the party started questioning and opposing Gandhi and other leaders of the Congress. Debi Chatterjee, a former professor of international relations at the Jadavpur University, in her book, Up Against Caste: Comparative Study of Ambedkar and Periyar, writes about the party under Periyar: It developed “a theory of rights, power and justice and a definition of community, which brought forth a new subject of history: rational, committed to reciprocity; equal, yet desirous of fraternity and above all free, bound only by the ideal of self-respect. That’s how the self-respect movement started.”

The goal of the movement was to create a caste-less society, free from the oppression of Brahmanical Hinduism. V Geetha and SV Rajadurai write in Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium, “To Periyar, caste was simultaneously system and ideology; it comprised a complex set of social relations as well as those principles which informed, sustained and justified these relations. As a system, caste served the interests of Brahmins who were its favoured agents and existed chiefly to gratify and perpetrate their sense of their superiority.”

In the first Self-Respect Provincial Conference held in 1929, Periyar urged all the non-Brahmins to drop their caste suffixes or surnames. This led to the formation of a bloc comprising Shudras and Adi Dravidas. Still, he could not encompass the whole of India. On the other hand, Chatterjee writes, Ambedkar had to “carve out space for his political movement in the cervices left by the contradictions between various Indian political parties and groups on one side and the colonial on the other. For most of his time, he sought the maximization of this space and eventually succeeded in bringing the Dalit issue to the national political agenda.”

Though Ambedkar had differences with Gandhi, he was accepted by the Congress as an alternative to Periyar. He, later on, wrote the Constitution that grants Dalits social, economic and political rights. The wider appeal of Ambedkar, in this sense, explains the efforts that the BJP makes to prove its “love” for Ambedkar—it is a political compulsion for them to try and appropriate him.

For Periyar, on the other hand, the BJP faces no such compulsion. Hence it can afford to criticize, even condemn him. The RSS and BJP drive their politics purely based on caste supremacy. They seek to polarise and divide South India, but want to remain unaffected by this in the rest of the country. To attack Periyar can therefore be seen as their strategy. In a way, encouraging casteist violence and intimidation tactics by young men of elite-castes, who seek to maintain patriarchal hierarchies, supports what is already in the DNA of the RSS-BJP combine.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

இந்த கருத்து வலைப்பதிவு நிர்வாகியால் நீக்கப்பட்டது.

பதிலளிநீக்கு