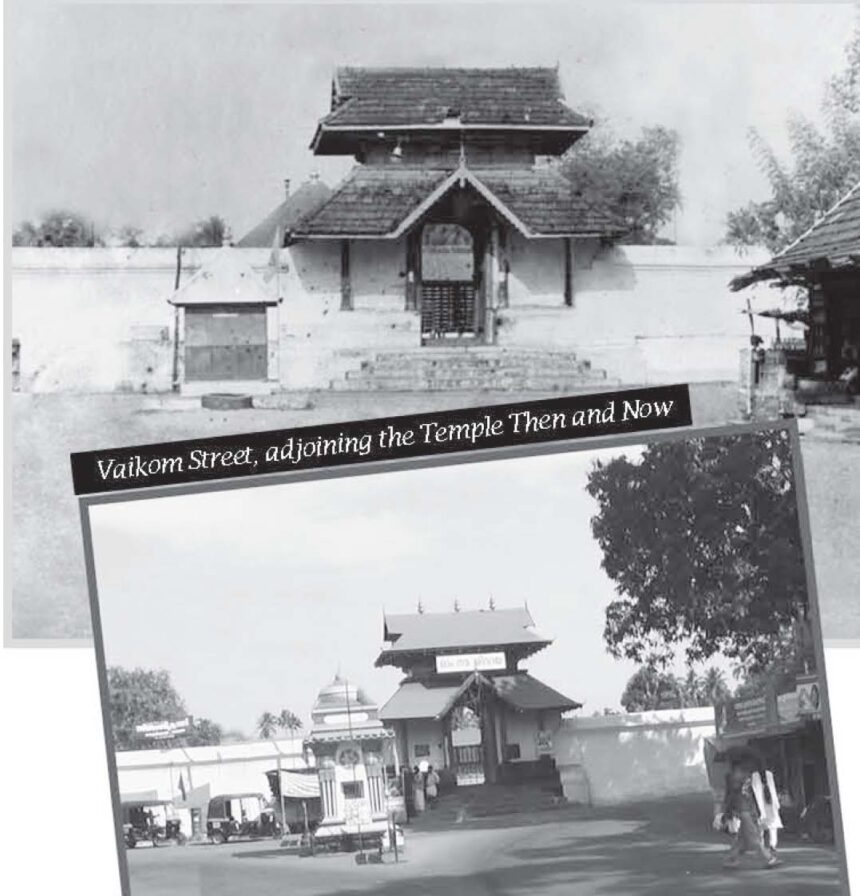

On the morning of March 30, 1924, three men dressed in khadi walked towards the Vaikom temple in the Princely State of Travancore (now part of Kottayam District, Kerala). Each belonged to a different caste—Govinda Panikkar, a Nair (Savarna) Bahuleyan, an Ezhava (BC) and Kunjappu, a Pulaya (Dalit). They were halted by the police about 50 yards from where Satyagrahis had begun a procession on the public roads that were prohibited to certain castes. A sign board first erected in 1905, banned people from marginalized castes using these roads.

Although these men didn’t reach the temple grounds, their efforts initiated an epic, year-long struggle that left a lasting impact on Kerala’s history. From that point forward, each day, three volunteers from different communities attempted to walk on the restricted roads. Though all the movement leaders were arrested within a week, the momentum of the Vaikom Satyagraha, the struggle against untouchability and discrimination, only grew stronger, attracting the attention of Mahatma Gandhi. Kerala is celebrating the centenary of the Vaikom Satyagraha, a pivotal moment in the fight against caste oppression in the country’s history.

The Vaikom Satyagraha, spanning 604 days from March 30, 1924, to November 23, 1925, became a pioneering movement for temple entry rights across India. This prolonged campaign set a powerful precedent for the broader push for equal access to religious spaces. The call for change was initially made by Ezhava leader T.K.Madhavan, who, in 1917, published an editorial in Deshabhimani advocating for temple entry for marginalized communities. As a journalist and social reformer who evolved along with the Sree Narayana Guru Dharma Paripalavan (SNDP) established by Sree Narayana Guru, T K Madhavan believed that caste oppression was the fundamental evil in the society. By 1920, inspired by Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement, Madhavan adopted a more direct approach, personally crossing the forbidden paths near the Vaikom temple as an act of defiance.

The movement gained significant momentum when a few leaders of Indian National congress (including Gandhi) threw its support behind the cause. In 1921, T.K. Madhavan, met with Gandhi and secured his endorsement for a large-scale campaign to open temples to all people. At the 1923 INC session in Kakinada, the Kerala Provincial Congress Committee formally prioritized the fight against untouchability. This marked the beginning of a widespread public campaign advocating for Hindu temples and public roads to be accessible to marginalized communities. Vaikom, with its prominent Shiva temple, was chosen as the site for this first historic satyagraha.

The Role of Periyar: Why the Vaikom Satyagraha is also remembered in Tamil Nadu

E.V. Ramaswamy, affectionately called Periyar by the people of Tamil Nadu, played a pivotal role in advancing the movement. Arriving in Vaikom on April 13, 1924, he assumed leadership at a time when the movement had stalled due to the arrest of its main leaders. Periyar’s tenure was marked by his unwavering stance against untouchability and caste discrimination, as he mobilized local communities and delivered powerful speeches to rally support. He organized protests and faced multiple arrests, spending a total of 74 days in jail during the struggle.

Periyar’s perspective on the movement differed significantly from Gandhi’s; he saw it as a broader battle against caste oppression rather than merely a reform within Hinduism. His emphasis on civil rights and equality energized the movement, leaving a lasting legacy in India’s anti-caste movement and earning him the title “Vaikom Veerar,” or the hero of Vaikom. Periyar’s leadership energized the movement and drew in broader participation, including women and activists from Tamil Nadu.

Last year, the centenary celebrations were inaugurated jointly by Chief Ministers Pinarayi Vijayan and M.K. Stalin, asserting the growing political solidarity between the two southern states. In their public addresses at a ceremony in Vaikom, both leaders emphasized the importance of building a stronger bond between Kerala and Tamil Nadu, drawing inspiration from the historic lessons of movements like the Vaikom Satyagraha.

Tamil Nadu Government also announced yearlong celebrations to mark the 100th year of the Satyagraha. Chief Minister M K Stalin announced in the Assembly that ‘Vaikom Award’ would be established to honour individuals and organisations beyond State borders who work for the oppressed class. This would be associated with the birth anniversary of Periyar which is observed as the ‘Day of Social Justice’ in Tamil Nadu.

Gandhi’s Role in the Vaikom Satyagraha

Although Mahatma Gandhi’s role in the Vaikom Satyagraha is frequently emphasized, the movement was shaped by various local leaders and activists with distinct visions and strategies. Historians differ in citing Gandhi as the leader of the movement, despite his presence elevating the movement to the national level. Satyagrahis like K.P.Kesava Menon often disagreed with Gandhi’s recommendations, asserting their independence in the struggle, as noted by historians.

Key figures like T.K. Madhavan were instrumental even before Gandhi’s involvement, advocating for temple entry rights as early as 1918. Madhavan’s grassroots efforts, including engaging with higher authorities and participating in Congress discussions, showcased a local approach that preceded Gandhi’s influence. Gandhi, in contrast, focused on reforming Hinduism from within, promoting moral transformation over direct confrontation—a stance that sometimes clashed with local leaders seeking immediate action against caste discrimination.

Indamthuruthi Mana: The Brahmin house where Gandhi was kept away On March 9, 1925, Mahatma Gandhi visited Vaikom to negotiate with upper-caste leaders who were fiercely opposed to the Satyagrahis’ demands. However, Gandhi himself was not permitted inside the Indamthuruthi Mana, the Brahmin home overseeing the Vaikom temple. Historians note that a temporary shelter was erected at a short distance from the Mana where Gandhi was offered a seat. Being a Vaishya and therefore of a lower caste in the social hierarchy, he was given a seat outside to avoid “polluting” the Mana by entering.

Gandhi was scheduled to meet Neelakandan Nambyathiri, then the head of Indamthuruthi Mana, a prominent family among 48 powerful Brahmin households. The Indamthuruthi family not only held influence over other Brahmin families but also controlled the Vaikom Mahadev temple. The term ‘Mana’ is traditionally used in Malayalam to denote the residences of Nambudiri Brahmins in Kerala.

If history has a way of correcting past mistakes, there is no better example than the evolution of Indamthuruthi Mana at Vaikom. Today, as one steps into the compound of Indamthuruthi Mana, the sight of a huge hammer and sickle on a red-painted platform captures sight-embodying the transformation of Kerala’s society. A red flag waves above the old structure, symbolizing these shifts. Since 1964, Indamthuruthi Mana has served as the headquarters for the Toddy Workers’ Union, affiliated with the Communist Party of India (CPI). Toddy tapping perceived as the traditional occupation of the Ezhava community—which was considered “untouchable” during the period of Vaikom Satyagraha—is at the heart of this union, founded in 1943.

Over time, the heirs of Neelakandan Nambyathiri, unable to sustain the Mana’s former status, were forced to sell parts of their property to make ends meet. Eventually, the Brahmin leaders at Indamthuruthi Mana decided to sell the estate to raise funds for a family wedding. The Communist Party expressed interest in acquiring it, raising funds from party workers and supporters. The transaction was completed on May 22, 1964, turning Indamthuruthi Mana into the headquarters of Vaikom Taluk’s toddy workers’ union affiliated to CPI.

According to historians participants of the Vaikom Satyagraha had varying motivations, with some viewing the struggle as a fight for civic rights, others focused on securing temple entry for all castes. This diversity of goals sometimes created internal tensions within the movement. Overall, the Vaikom Satyagraha reflected a complex blend of activism and ideologies, multi layered, revealing a rich, versatile struggle for social justice and equality.

Courtesy: ‘The Modern Rationalist’, Dec. 2024